How reliable are the website popularity rankings like the Alexa top one million that many of us use in our research? We analysed four ranking lists and discovered the impact they have on research results and how easily they can be manipulated. For this reason, we created Tranco, a new improved popularity ranking list.

Researchers, security analysts, and companies frequently use popular sites to evaluate the prevalence of security and privacy practices on a representative sample of the web. Moreover, popular sites are often assumed to be benign and are therefore whitelisted e.g. in Quad9’s abuse-blocking DNS resolver. Browser vendors such as Mozilla also take the popularity of these websites into account when making important security decisions.

Commercial providers such as Alexa, publish daily rankings of the most popular websites, but up until now, their validity has rarely been questioned. Their properties and implications have only recently started to be analysed. To gain more insight into how reliable such data is, we sought to answer the following three questions:

- How do such rankings affect research?

- Can malicious actors abuse rankings?

- How do we improve such rankings?

How Do the Inherent Properties of Popularity Ranking Lists Affect Research?

We studied the Alexa, Cisco Umbrella, Majestic, and Quantcast rankings, as these are free and more likely to be used by researchers and analysts. These rankings all use different data sources and scoring methods to compute their ranking:

- Alexa mainly relies on end users installing a browser extension that sends all visited URLs back to Alexa;

- Cisco Umbrella counts the number of IPs that resolve a domain through its OpenDNS resolvers;

- Majestic counts the number of subnets that host a web page linking back to a domain;

- Quantcast mainly ranks sites that report visitor counts through an analytics script.

These different vantage points and ranking methods suggest that the rankings may exhibit diverse characteristics and are composed differently. We analysed several of their properties, and in particular, those that can have implications on their suitability for research.

Similarity

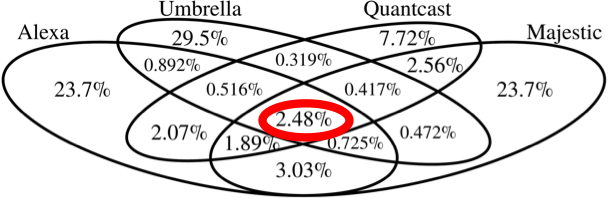

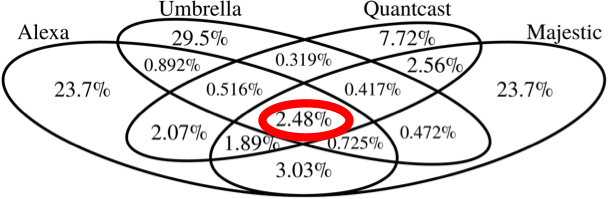

In Figure 1, we show the average number of sites that the rankings agree upon per day. We found that the four lists only agree on 2.48% of popular domains - the four lists combined contain around 2.82 million sites but agree only on around 70,000 sites. There is little agreement between these lists, which makes their claim of containing the most popular sites on the web somewhat questionable.

Figure 1: The daily average intersection between the four lists from January 2018 to November 2019

Stability

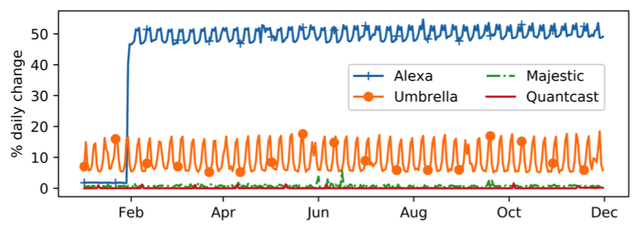

The stability varied significantly across the four lists. As shown in Figure 2, we see that Majestic’s and Quantcast’s lists are the most consistent. They usually shift around 1% per day, while for Umbrella’s list this climbs to 10% on average. Since 30 January 2018, almost half of the top million entries on Alexa's list change every day. This was actually the result of an unannounced and previously known change in Alexa’s ranking method. They switched from averaging over one month’s worth of data to using only one day of data, causing much more volatility.

There is a trade-off in the desired level of stability for use in research. A very stable list provides a reusable set of domains but may incorrectly list sites that suddenly gain or lose popularity. This means that you do not see sudden jumps or newly added domains. A volatile list that changes a lot in terms of top popular domains, however, may introduce large variations in the results of longitudinal or historical studies.

Figure 2: The intersection percentage of each provider's list over two consecutive days

Responsiveness

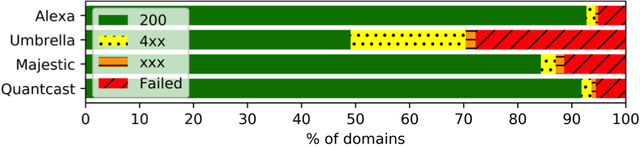

Figure 3 shows the HTTP status code reported for the root pages of the domains in the four lists (codes starting with 2, 4 and all other HTTP status codes). In terms of responsiveness, 5% of Alexa’s and Quantcast’s lists and 11% of Majestic’s list could not be reached. For Umbrella, this jumps to 28%. Moreover, only 49% responded with HTTP status code 200, and 30% reported a server error. Most errors in Umbrella are due to the fact that it does not filter out invalid or not configured (sub)domains. Unresponsive sites reduce the effective sample that is studied, potentially making the results less representative of the entire Internet.

Figure 3: The responsiveness and reported HTTP status code across the lists

Benignness

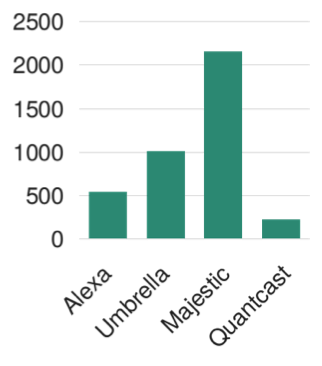

As checked against Google Safe Browsing on 31 May 2018, 0.22% of Majestic’s domains were flagged as potentially harmful - identified as malware sites. However, all lists rank at least some malicious domains. In Alexa’s top 10,000, four sites are flagged as performing social engineering (e.g. phishing). One site in Majestic’s top 10,000 serves unwanted software (for absolute counts, see Figure 4). The presence of these sites in Alexa’s and Quantcast’s lists is particularly striking. Users would have to actively ignore the browser warning in order to trigger data reporting for Alexa’s extension or the tracking scripts.

Figure 4: Malicious websites per list

Given the presence of malicious domains on these lists, the practice of whitelisting popular domains, as done by some security analysis tools, is particularly dangerous (check this blog post and this forum entry). Quad9’s DNS-based blocking service whitelists all domains on Majestic’s list, exposing its users to ranked malicious domains. As Quad9’s users expect harmful domains to be blocked, they are under the impression that the site is safe to browse; this makes the manipulation of the list very interesting to attackers.

How Can These Rankings Be Manipulated?

The data collection processes of popularity rankings tend to rely on a limited view of the Internet, either by focusing on one specific metric or obtaining information from a small population. This implies that targeted small amounts of traffic can be deemed significant on the scale of the entire Internet and yield good rankings. Furthermore, the ranking providers generally do not filter out automated or fake traffic or domains that do not represent real websites - further reducing the number of domains with real traffic in their lists.

As several security vendors make browsing decisions based on such rankings, malicious actors could have incentives to manipulate rankings. They can do so by whitelisting their own malicious domains, hiding malicious practices in other domains, or affecting broader policy decision by changing the perceived prevalence of security issues and practices.

We investigated whether malicious actors are able to abuse the trust put into popularity rankings by manipulating them through forged traffic to the ranking providers. We proved that all four rankings are susceptible to at least one low-cost, a low-effort technique that allows for large-scale manipulation.

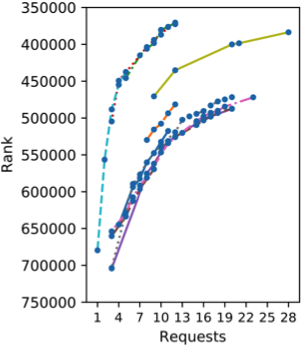

The most surprising result was that the widely-used Alexa list was particularly vulnerable to manipulation. As little as one request yielded a rank within the top million. We achieved rank as high as 370,461 with only 12 requests as showed in Figure 5 (albeit in the weekend, when the same number of requests yields a better rank). As they rely mostly on their “Traffic Rank” browser extension that reports all page visits, we forged traffic by installing the extension in a Chrome browser and then automatically visited our domain.

[1] For pages loaded over HTTPS, the path is obfuscated.

Figure 5: Ranks obtained in the Alexa list. Ranks on the same day are connected

Through inspection of the extension’s source code and traffic, we found that upon page load, a GET request with the full URL of the visited page is sent alongside the user’s profile ID and browser properties to an endpoint on data.alexa.com. This endpoint can be an alternative way to submit fake page visits without the need to use an actual browser, further reducing the overhead in manipulating many domains on a large scale.

We found that Alexa did little to no verification on our traffic. Our test domains did not have to actually exist and be registered. We could resolve them locally to give the impression that they exist. They were never visited by Alexa, they did not have to be previously seen by Alexa, and Alexa did not impose any limits on the number of user profiles that could be created.

While we focused only on the manipulation of Alexa, we succeeded in inserting our domains into all popularity rankings. For more details of these manipulation techniques, we invite you to read our full paper.

The table below shows a summary of the efforts and resources needed to manipulate each of the popularity lists. In short, simple, low-cost techniques make some the manipulations possible on a large scale.

Table 1: Summary of manipulation techniques and their estimates cost

| Provider | Technique | Monetary | Effort | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa | Extension | none | medium | low |

| Analytics scripts | medium | medium | high | |

| Umbrella | Cloud providers | low | medium | low |

| Majestic | Backlinks | high | high | high |

| Reflected URLs | none | high | medium | |

| Quantcast | Analytics scripts | low | medium | high |

TRANCO: A New Improved Ranking

Now the question is: how can improve existing rankings, and what else can we do to ensure that researchers and analysts can continue studying the current state of the Internet?

We contacted all providers with suggestions on how to improve their rankings, but commercial interests prohibit them from implementing these measures that discourage (large-scale) manipulation. Therefore, we took it upon ourselves to design and create an improved ranking. To this extent, we introduce TRANCO, an approach that researchers and industry players can use to obtain lists with more desirable and appropriate properties.

TRANCO combines all currently available ranking data with the goal of improving the properties of popularity rankings for research. At the same time, it removes the respective deficiencies of the existing rankings. The existing rankings average across a chosen period of time and set of providers. Additional filters can be applied, e.g. filtering out unresponsive or malicious sites. For ease of use, we provide standard lists that can be readily used, but also allow the creation of highly-configurable combined lists. At the same time, certain properties may be beneficial depending on the use case. For instance, researchers may want to choose specific providers, vary the averaging period to change stability or only keep domains listed by multiple providers for multiple days to avoid briefly popular (or manipulated) domains.

To improve the stability of our combined lists and the agreement on which domains are actually popular, TRANCO's default setting uses the rankings of all four providers for a period of 30 days. We evaluated these standard options on their improvements to the properties important for research and found that no list has a disproportionate influence on the combined list and that our TRANCO list changes on average less than 0.6% every day. This means that our list can be used even in longitudinal settings, as the set of domains does not change significantly.

We also emphasise properties that are valuable for performing sound and valid research. Our source code is available on GitHub to provide full transparency of how our lists are generated. Moreover, when generating and downloading lists on our TRANCO website, we create a permanent ID for each list with a corresponding web page that explains in full detail which parameters were used to create the list. When researchers and analysts report this ID in their findings, anyone can then consult the exact list of domains used anytime in the future, greatly enhancing the reproducibility of the research.

Other Relevant Studies

Popularity rankings have only very recently started to be thoroughly analysed by researchers. Scheitle et al. focused on the impact of the Alexa, Majestic and Umbrella lists on Internet measurement researchers. They assessed their structure and stability over time, discussing their usage in (Internet measurement) research through a survey of recent studies, calculated the potential impact on their results, and drafted initial guidelines for using the rankings. We focus on the implications of these lists for security research, expanding the analysis to include representativeness, responsiveness, and benignness. Furthermore, we demonstrate the possibility of malicious large-scale manipulation and propose a concrete solution to these shortcomings by providing researchers with improved and publicly available rankings.

Briefly after our study, Rweyemamu et al. looked at website rankings in a complementary manner, studying various additional characteristics of top domain lists in more detail. For example, they quantified the ‘weekend effect’ in Alexa and Umbrella that causes these rankings to have clear distinctions between the domains ranked in the workweek and in the weekend. Additionally, they have collected all currently proposed best practices regarding the use of top domain lists in the (security) research community.

Conclusion

Rankings of the most popular websites are in active use by researchers, security analysts, and industry players. However, their methods and properties were largely unknown until now. We performed an extensive analysis of four rankings, evaluating their characteristics and the effects on research results. We found that all rankings can be manipulated with ease and therefore on a large scale. In particular, the ubiquitous Alexa list could be manipulated with just one single forged request. Given the real-world security effects of these lists e.g. on whitelists or policy decisions, attackers may want to abuse these manipulation techniques to make malicious domains appear benign or to influence the perception of security issues.

To allow the community to continue the important work of measuring the current state of the web, we developed TRANCO, a new approach to creating rankings that aggregates existing lists intelligently and improves those properties that are important for performing sound and valid research. We publicly share our method as well as regularly update lists as an accessible and verifiable resource to obtain popularity rankings in the future.

If you are interested in downloading the daily updated default TRANCO list or finding more information on how it is created, please visit our website and consult our full research paper:

- Le Pochat, Victor, Tom Van Goethem, Samaneh Tajalizadehkhoob, Maciej Korczyński, and WouterJoosen. "Tranco: a research-oriented top sites ranking hardened against manipulation." In Proceedings ofthe 26th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. Internet Society, 2019.

Appendix 1: Top Website Rankings

Alexa

Alexa, a subsidiary of Amazon, publishes a daily list consisting of one million websites since December 2008.

Only pay-level domains[1] are ranked, except for subdomains of certain sites that provide ‘personal home pages or blogs’ (e.g. tmall.com, wordpress.com). The ranks calculated by Alexa are based on traffic data from a “global data panel”, with domains being ranked on a proprietary measure of unique visitors and page views, where one visitor can have at most one page view count towards the page views of a URL (see the Alexa FAQ). Alexa states that it applies “data normalization” to account for biases in their user panel (See How are Alexa's traffic ranking determined?).

Cisco Umbrella

Cisco Umbrella publishes a daily list consisting of one million entries since December 2016. Any domain name may be included and will be ranked based on the aggregated traffic counts of itself and all its subdomains. The ranks calculated by Cisco Umbrella are based on DNS traffic to its two DNS resolvers (marketed as OpenDNS) and claim to amount to over 100 billion daily requests from 65 million users. Domains are ranked on the number of unique IP addresses issuing DNS queries for them (see the Cisco Umbrella bog). Umbrella’s data collection method means that non-browser-based traffic is also accounted for. A side-effect is that invalid domains are also included (e.g. internal domains such as *.ec2. internal for Amazon EC2 instances, or typos such as google.conm).

Majestic

Majestic publishes the daily ‘Majestic Million’ list consisting of one million websites since October 2012. The list is mostly comprised of pay-level domains but includes sub-domains for certain very popular sites (e.g., plus.google.com, en.wikipedia.org). The ranks are based on backlinks to websites, obtained by a crawl of around 450 billion URLs over 120 days, changed from 90 days on 12 April 2018 (see the Majestic FAQ and blog). Sites are ranked on the number of IPv4 /24) prefixes that refer to the site at least once. This means only domains linked to from other websites are considered, implying a bias towards browser-based traffic, however, without counting actual page visits. Similar to search engines, the completeness of their data is affected by how their crawler discovers websites.

Quantcast

Quantcast publishes a list of the most visited websites in the United States since mid-2007. The size of the list varies daily, but usually is around 520,000 (mostly) pay-level domains. Subdomains reflect sites that publish user content (e.g. blogspot.com, github.io). The list also includes ‘hidden profiles’, where sites are ranked but the domain is hidden. The ranks are based on the number of people visiting a site within the previous month, and comprises ‘quantified’ sites where Quantcast directly measures traffic through a tracking script as well as sites where Quantcast estimates traffic based on data from ‘ISPs and toolbar providers’ for traffic in the United States, with only quantified sites being ranked in other countries.

Footnotes

[1] A pay-level domain (PLD) refers to a domain name that a consumer or business can directly register, and consists of a subdomain of a public suffix or effective top-level domain (e.g. .com but also .co.uk).

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.