The current combination of RIPE policies and rules for RIPE NCC membership enable IPv6 stockpiling. And what might sound like an unlikely activity is not only happening, but is actually on the rise. Here we look at the trends and some of the potential consequences and ask where we go from here.

In ancient Greek mythology, Cassandra of Troy was blessed with the gift of prophecy by the god Apollo. However, when she refused his advances, he cursed her so that no one would believe her predictions. Cassandra foretold the fall of Troy and warned her fellow citizens not to let the Trojan horse enter the city. Sadly, her warnings went unheeded, ultimately leading to the city's destruction.

While there are a few obvious differences, I can't help feeling a little like Cassandra when I caution during several RIPE meetings [1] [2] about the risks of IPv6 stockpiling. Much like Cassandra's dire predictions, concerns about the unchecked accumulation of IPv6 address space have often been ignored.

Before going into the specifics, it's important to be clear that all of the behaviour that we describe in this article is consistent with existing RIPE policy and procedural guidelines for our service region. The existing framework has so far been very accommodating in order to facilitate IPv6 deployment. In fact, one could argue that these organisations are maximising the opportunities available to them and have developed a successful business model.

The purpose of this article is to shed light on the consequences and collateral effects of this business model for the broader membership base, the RIR system and the Internet ecosystem in our region - effects that may not be readily apparent even to those members who are driving this trend. Additionally, it aims to initiate a discussion on the best path forward to ensure a thriving ecosystem for all participants.

What is the situation?

When the term "IPv6 stockpiling" is mentioned, it often creates surprise. Historically, discussions surrounding IPv6 were focused on making it easier for organisations to access and deploy large IPv6 blocks. Several policy adjustments made by the RIPE community in recent years aimed to promote IPv6 adoption. For instance, in 2015, IPv6 transfers became viable in the RIPE region after consensus was reached on a corresponding policy proposal. Subsequently, in 2018, a policy update clarified that each LIR account could obtain a /29 IPv6 allocation (rather than each organisation). Initially, these changes were anticipated to address limited, specific scenarios, such as handing over live networks or assisting members with multiple LIR accounts in simplifying IPv6 deployment across segmented company structures.

However, the actual outcomes over the past years have deviated from those expectations. Many members with multiple LIR accounts have requested separate IPv6 allocations for each account, only to later consolidate them into one account or swiftly transfer them to other members. In some cases, members have obtained IPv6 allocations solely to transfer them to another member within days.

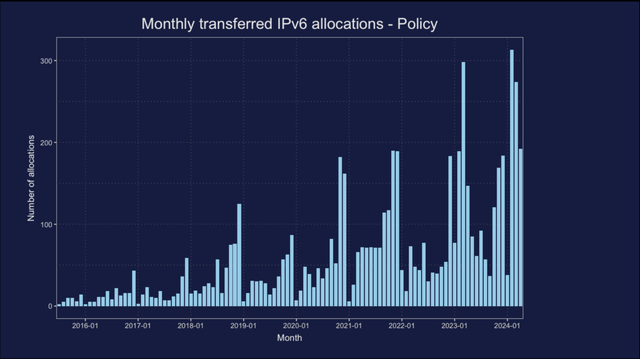

Since the introduction of IPv6 transfers, over 6,000 IPv6 allocations have changed holdership via a policy transfer, accounting for approximately 25% of all IPv6 allocations ever distributed by the RIPE NCC. And this trend is increasing.

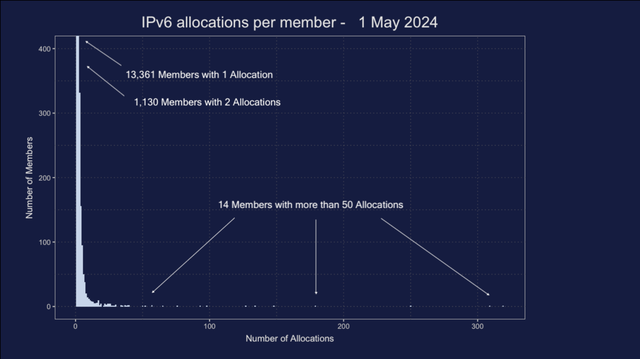

While certain changes in holdership align with the original policy intentions, there is a noticeable aggregation of IPv6 space among a few members who now hold dozens or even hundreds of IPv6 allocations.

What do we know?

When this observation was presented to the RIPE community at RIPE 87, people were curious about the purpose of this stockpiling. We have been looking into publicly available data to investigate this.

In the years 2015-2019, more and more organisations opened additional accounts and set up new companies to obtain more than one final /22 IPv4 allocation from the last /8. Several of these members also requested IPv6 for every LIR they controlled. When the extra LIRs were later consolidated, or the companies merged, several members ended up with dozens of IPv6 allocations. By April 2020, the largest such member had accumulated 91 allocations, equivalent to 728 /32s. In recent years, however, we have seen an increasing amount of transfers originating from members who already had sizeable IPv6 holdings. This caused a fast rise in the maximum number of IPv6 allocations held by a single member.

When looking at the top 10 stockpiling members, 7 possessed only one LIR account and accumulated their IPv6 allocations exclusively through transfers from other members. Also noteworthy is the very targeted approach by some members, who joined as recently as 2023 or even 2024 and yet have already acquired numerous IPv6 allocations within this short time.

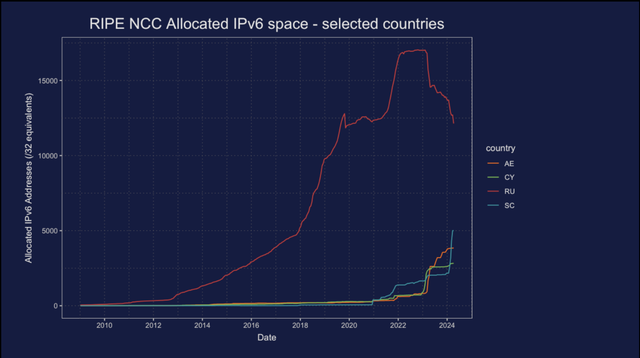

The scale of these IPv6 transfers to certain members is significant enough to impact national IPv6 statistics. Notable increases can be seen in the countries where these members are located, alongside a corresponding decline in the countries where the offering parties are based. One especially prominent example is Russia, which saw a reduction in IPv6 allocations by approximately 25%, bringing it back to allocation levels seen in 2019.

Allocated vs. routed

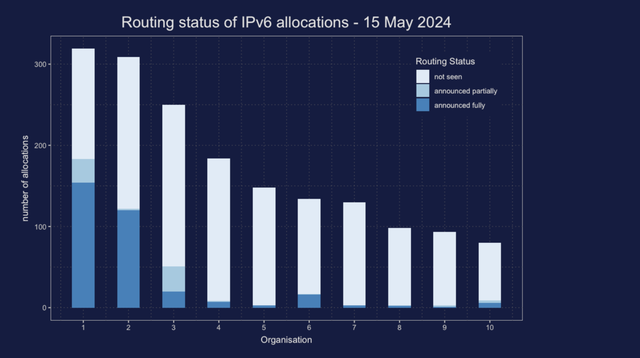

One question that has frequently been raised is whether and how these IPv6 blocks are being utilised. When we examine the routing aspect closely, we observe a diverse landscape. When we focus on the top 10 members with the most IPv6 allocations, it becomes apparent that most are literally stockpiling IPv6, with little of this address space being actively used.

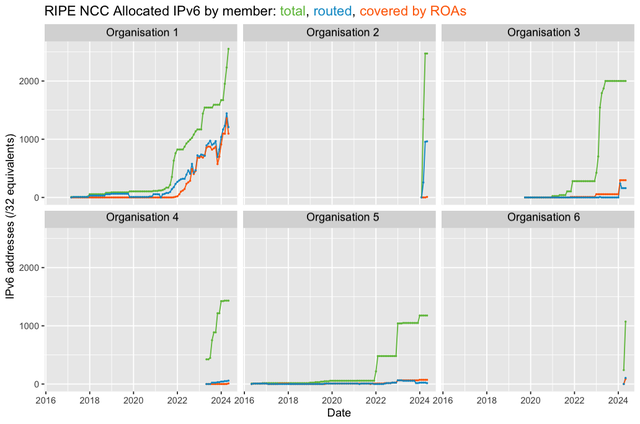

Looking a bit deeper into the routing history of the six largest members, which also have the most notable activities, we can see that some members are already routing significant portions of their allocations and have even established ROAs.

While we can't definitively determine whether these announced ranges are actively in use and, importantly, in compliance with RIPE policies, it shows that some work is done with these allocations.

Why should we care?

Whenever concerns about excessive IPv6 consumption arise, a common response is to point to the vastness of the IPv6 address space. So far 1/252th of global unicast IPv6 space has been allocated to the RIPE NCC, and all RIRs together have received only around 1.4% of the IANA reserve.

While these figures may seem insignificant in absolute terms, it's crucial to consider them in relation to the total address space allocated by the RIPE NCC. Much like the ocean, while the majority is unexplored, most attention is directed towards the small portion that has been mapped and segmented.

The 14 members with over 50 IPv6 allocations now collectively hold nearly 9% of all IPv6 space allocated by the RIPE NCC. Additionally, three of them rank among the top 10 IPv6 holders.

| IPv6 allocations | IPv6 allocated /32s | Percent of total | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 8193 | 4.54 | FR |

| 1 | 8192 | 4.54 | DE |

| 1 | 8192 | 4.54 | GB |

| 5 | 4107 | 2.28 | IT |

| 12 | 4098 | 2.27 | SE |

| 319 | 2552 | 1.41 | SC |

| 309 | 2472 | 1.37 | SC |

| 3 | 2057 | 1.14 | GB |

| 2 | 2056 | 1.14 | PL |

| 250 | 2000 | 1.11 | CY |

This indicates the first challenge of these stockpiling activities. Each LIR is entitled to receive one /29 IPv6 allocation with only minimum justification requirements. The RIPE community believed that this block size, which contains eight times as many /64 subnets as IP addresses from the entire IPv4 space, was enough for the IPv6 deployment plans of nearly all organisations.

If a company thinks it needs more space, the IPv6 policy permits them to request more after providing details like estimated user numbers and scheduled network size to the RIPE NCC. This ensures that the proposed IPv6 deployment aligns with IPv6 policy and best current operational practices (BCOP) for IPv6.

When a member accumulates numerous /29 allocations via the transfer market, this oversight is missing, because the evaluation criteria for larger IPv6 allocations are circumvented. It's possible that these members genuinely require such a large amount of address space in compliance with policy, but we, the RIPE NCC, just don’t know.

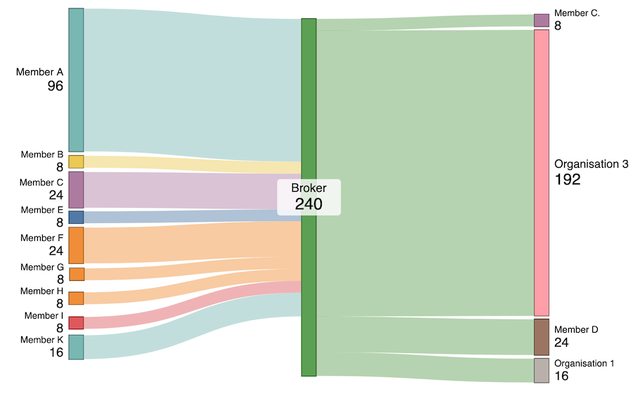

Secondly, it places a heavy burden on our Registry team and consequently adds extra costs for our members, who finance our operations. While evaluating a request for a large IPv6 allocation may take some time and effort due to documentation requirements, the workload caused by stockpiling far exceeds this. To accumulate 300 IPv6 allocations, a corresponding number of requests must first be submitted by various members. Although these requests are processed relatively quickly, each one still requires about 20-30 minutes of work for our Registration Services team, totaling 100-150 working hours.

The next step, actually processing 300 transfer requests, even with some automation, requires around 50-60 minutes each. This adds another 300 hours to the total. To put it into perspective, one of our Internet Resource Analysts would have to work continuously for about two weeks just for one member to gather that many IPv6 allocations in this manner.

Thirdly, we've observed that some members have created a secondary market to offer large IPv6 blocks. While the RIPE community and the RIPE NCC have always encouraged members to distribute IPv6 to their customers and promote IPv6 deployment, some members have taken this activity to a new level. Entire allocations or, according to one advertisement we found, “100x /29 ranges” are being offered for rent.

While it may initially seem beneficial that non-members can acquire an IPv6 block of the same size as a member but at a significantly lower cost than a RIPE NCC membership, there are several negative effects for the Internet ecosystem as a whole that cannot be overlooked.

These organisations are less likely to become RIPE NCC members. This reluctance hampers the growth of our membership base, thereby negatively impacting the entire membership. The RIPE NCC as a membership organisation thrives on diversity and growth. We encourage organisations from different sectors - including enterprises, government bodies, academic institutions, as well as cloud and service providers - to obtain and register their own resources.

Furthermore, when the costs for existing members increase due to the actions of a single member, it creates a financial burden that affects everyone. The RIPE NCC operates on a collective funding model, where costs are distributed among members. If one member's activities result in increased costs for the organisation, all members are required to absorb this through higher fees or reduced benefits.

Organisations that choose to rent IPv6 from these members may also expose themselves to unexpected risks. Once they have deployed their networks on these IPv6 ranges, they become highly dependent on any future business decisions made by that member. This could include significant changes in pricing models or even the termination of their RIPE NCC membership, resulting in the deregistration of allocations with live customer networks.

While we cannot speculate about or judge the business plans of these members, these risks are more than hypothetical. During the IPv4 runout and subsequent shortage, some members presented their customers with a dilemma: accept significantly higher prices or else renumber their networks. While there is no risk of an IPv6 shortage, the challenges of renumbering remain real and are even higher with IPv6. Anyone with experience in such renumbering activities can confirm how work- and time-intensive they can be.

Lastly, we should also consider that such blocks might attract actors who prefer to operate discreetly. For instance, they may intend to use these IPv6 blocks for spamming or other malicious actions. Once a block is blacklisted and tainted, it is abandoned, and the activities continue on a different, fresh IPv6 block. As a regional Internet registry, we are accountable to competent authorities and governments, which places upon us the responsibility to ensure that the resources we steward are not misused or abused.

This behaviour is likely to draw the attention of law enforcement, who will then face challenges in identifying the actual perpetrator of these activities, potentially leading them to seek clarification from either the member responsible for the resources or the RIPE NCC. There may also be challenges from competent authorities and governments regarding how such unclear ownership situations are possible within the current RIR system, possibly leading to high-level criticism of the effectiveness of the RIPE community’s policy-making in general.

Where do we go from here?

To summarise, the observed stockpiling activities present multiple challenges:

- Insufficient oversight regarding the utilisation of accumulated IPv6 allocations in accordance with RIPE policies and BCOPs

- Heavy burden on the Registry team and increased costs for members due to stockpiling activities

- Impact on membership base growth and financial burden for existing members

- Creation of a secondary market for renting large IPv6 blocks

- Risks for organisations when deploying their networks on rented IPv6 allocations

- Potential for concealed and malicious activities using rented IPv6 blocks, leading to reputational damage and law enforcement attention

These should be enough points for the RIPE community to consider if this (admittedly interesting) business model needs a closer review. The community should evaluate whether the opportunities this creates for a small minority outweigh the potential impacts it could have on the wider ecosystem we operate in.

As these activities are enabled by the current combination of RIPE policies and rules for RIPE NCC membership, a more strategic review of the entire system might offer a long-term solution, as recently suggested in another RIPE Labs article, Building a Stable Future for the RIPE NCC. Since such fundamental changes are still in the early stages of discussion and will certainly require time, in the meantime, the community should consider whether our IPv6 policies need a review, or at the very least, whether our understanding and application of the current policy should evolve. IPv6 has secured its position in the market, and perhaps promoting and supporting growth at any cost should be replaced by a more careful approach to how IPv6 is actually used.

I hope this warning will be heeded. It’s time to ask ourselves if we are welcoming a Trojan horse into the IPv6 world and, if so, what we can do about it.

Comments 3

Jordi Palet Martinez •

I feel that the main problem in this region is that we allow a "wild west" by not requiring justification of the need in transfers and we should resolve that. Same with the lack of policy regarding leasing. All this clearly goes against the community and the membership. To make it worst, address-policy WG chairs ignore proposals from community members which will facilitate the allocation of IPv6 (avoiding the need for at least some of those transfers), against the PDP, and discriminate those members by "selecting" by themselves that a later submitted policy proposal is accepted or presented in the WG instead of the 1st one already submitted much ahead, disallowing the normal community defined process, presumably even against the code of conduct. No wonder that the community just don't care and avoids investing time in discussing topics that the staff warned about and some participants submitted proposals that have been ignored, for example for the ASs. Going back to the specific topic in this posting, it will be interesting to know if the NCC is getting escalated abuse reports coming from those IPv6 blocks or any other information that can tell us how much of that space is being used for good and bad.

Andrejs Guba •

Thank you very much for the research. I would like to share my opinion on the conclusions made at the end: In fact, the accumulation relates only to 2 (or 3?) real members (SC and CY). Most likely, the two SC members actually represent one person (this needs to be investigated based on the information about the initial transfers). The other members received their blocks a long time ago, and they were originally large (as seen from the number of allocations). The described problem with the load on the RIPE team is also true but only partially. The highest activity occurred once when member SC transferred their “assets” from RU to SC and when CY gathered everything under one account. How many accumulation activities (transfers) have there been since then? How does this activity compare to IPv4? The last 5 points are equivalent to IPv4, which already has an established rental market. Is anyone asking the same questions about IPv4?

Marco Schmidt •

Hello Andrejs, Thank you for your feedback and questions. Our research showed that the top 10 stockpiling members are spread across several countries. Additionally, most of them have recently received numerous IPv6 allocations, primarily through transfers. For accumulation activities, you can get some indication from our IPv6 transfer statistics, which lists all IPv6 allocation transfers, including the offering and receiving parties. https://www.ripe.net/manage-ips-and-asns/resource-transfers-and-mergers/transfer-statistics/within-ripe-ncc-service-region/ipv6-transfer-statistics/ Comparing this activity with IPv4 requires taking into account several differences, especially the time component. The RIPE NCC currently provides a /24 IPv4 allocation to new LIRs only after a waiting period of 16 to 18 months, while all LIRs qualify immediately for a /29 IPv6 allocation without needing to supply any additional information. Further IPv4 can only be transferred after a holding period of 24 months, while no such limitation exists for IPv6. This results in much more rapid activities with IPv6, where allocations were sometimes requested and then transferred within a few days.