RightsCon is a huge conference on human rights in the digital age. 8,500 attendees meet this week to discuss Internet shutdowns, content governance, data protection, digital economy, and more. As these discussions benefit from more input from the technical community, we’ll be updating you on what we get to see of the 500+ sessions.

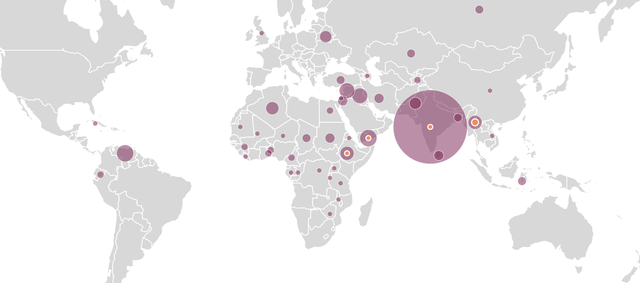

Let's start with some stats and a little more background on the event. With such healthy attendee figures - 8,500 attendees, 67% of which are newcomers - it won't come as a surprise that there are 164 countries represented. Kudos to their programme committee for handling over 1,000 session proposals (although I must admit the 500-or-so approved sessions were quite overwhelming to sift through). In any case, a remarkable feat! They seem to have a strong stream of finances, with sponsorship from the Dutch, Danish, Swedish, German and Canadian governments as well as big ticket players from the online world. I won't lie, I'm impressed.

In the opening session Brett Solomon, Executive Director of Access Now (the organisation behind RightsCon) gave us an overview of what the event has achieved in the 10 years of its existence. It's helped develop norms like the Toronto declaration on AI, launched movements such as the #KeepItOn coalition to stop Internet shutdowns, kickstarted campaigns such as #WhyID calling for rights-respecting identity systems, started #BanBS, pushed for the banning of biometric recognition technologies in publicly accessible spaces, mobilised through the Arab spring and its aftermath (although one of the speakers from Egypt is still in jail over his activism).

And over the years, there were also certain negative developments that provoked much discussion, such as the Snowden revelations and the Cambridge Analytica scandal. But, as Brett pointed out, it's not all bad news. He recalled the shouts of joy when the Indian Supreme Court struck down Section 66a of the Information Technology Act used to arrest bloggers and critics online.

To frame discussion for the coming week, he referred us to the joint statement published just before the event by the six UN Special Rapporteurs in attendance, in which they express their increasing concern that states continue to use the Internet and digital technologies to stifle dissent. He also pointed to the report by the Digital Security Helpline on technical attacks and vulnerabilities facing civil society, which recently recorded its 10,000th case.

European Regulation

The EU regulation proposals published in December 2020 (DSA, DMA, NIS 2) got people talking. Panelists agreed that it is difficult for technical organisations to determine where the balance lies and what measures are appropriate for issues like content, as it's not their area of expertise. This is why they welcome the EU's proposals as an attempt to introduce more legal clarity and certainly as well as a level the playing field. Some of the drawbacks of the proposals can be attributed to almost any piece of legislation - the need to sharpen definitions, to align better with other laws (such as the Copyright Directive, the Terrorist Content Regulation) and to test out the co-regulatory process, which has the potential to become quite sophisticated. Panelists praised the risk-based approach: assigning different levels of obligations to players in different categories, although acknowledge it could be difficult for those that are on the boundary of two categories.

The NIS 2 proposal drew criticism concerning its handling of DNS services, where its scope is considered to be too broad - covering everyone all the way to the enthusiast with a resolver on their laptop. The fact that the scope also includes root operators can prove counterproductive, because it could actually reduce the number of operators, as they try to avoid being regulated. The IANA transition was done specifically to reduce the influence from any specific country and the regulation in its current form counters that. Should other regions respond with their own laws, this would create an even greater complexity for DNS operators - ultimately leading to a less resilient system.

Finally panelists discussed expanding the current DSA provisions obliging platforms to give access to data to researchers who can scrutinise their work and assess evolving risks. Participants suggested expanding this provision to include consumer protection and other civil society organisations. However, it was also acknowledged that more clarity needs to be given on the type of data that needs to be shared, how it can be used and handled (as some of it could be commercially sensitive) as well as procedures to ensure platforms are not overwhelmed with requests.

Social and Environmental Factors in Tech

According to Electronic Watch, clean and fair electronics do not exist at the moment. There is the environmental impact of getting the raw materials, the electricity used to produce them, as well as the electricity they use throughout their life, the shipping, the packaging, and of course the end-of-life impact (which probably means ending up in a landfill in a developing country). There is also the social impact of the appalling conditions of the workers getting those raw materials or those involved in the manufacturing and the rest of the supply chain. Patience Luyeye (Amazone Advisors) spoke of children as young as seven working with no safety equipment in Congo's cobalt mines that provide 60% of the world's supply. Women employed in those mines under similar conditions don't just suffer the health consequences themselves, but pass them on to their offspring.

So what can we, society, the world, do, to improve this situation?

Money talks. One of the most effective ways to push for change is when large public and private buyers include social and environmental criteria in their purchasing practices and ask suppliers to comply with certain standards. Rather than only looking at labels and certification, they should listen to independent sources, workers and communities. And when the buyers lack the expertise and resources for such research they can turn to civil society who have that personal connection. The Global Electronic Council recently published Purchasers Guide for Addressing Labor & Human Rights Impacts in Technology Procurements.

Worker representation is also a key to get meaningful change. Sadly, a lot of those workers are in countries where such unions or associations are not allowed.

And finally, change can be spurred by better reporting. Sustainability reporting is not new to a lot of large companies but is now catching on with the tech industry as a whole. We can learn from each other - both from mistakes and best practices. Yet doing so requires good reporting and at the moment this rarely happens. Oftentimes the sustainability reports provide a lot of data, without explaining what it means, with no context and are overall difficult to read. They are also rarely transparent about negative results or setbacks. At this stage, a good report is not one with amazing results - it is an honest report.

New IP and the Core Principles

How many of you think about the big picture, the strategy and architecture behind the Internet in their day-to-day work? We are used to updating, patching and from time to time deploying entirely new tools, protocols and standards. But we take for granted a lot of the elements and the thought behind how the Internet works. There is a set of core principles that have helped the Internet to develop from what it was in 1969 to what it is today. The Internet was not created or designed with the aim to become a global network, but those principles allowed it to develop into one. Principles such as: each distinct network has to stand on its own, be autonomous; communication happens on a best effort basis; there is no central control. These principles have shaped the development of several layers that are independent from each other - "dumb" layers at the core, that transport traffic indiscriminately and a smart app layer at the edge, where all the innovation happens (here I'm talking about the innovation the Internet has spurred in every sphere of human life, not to say that there is nothing new happening in the layers below).

A lot has been said about NewIP and I will not be repeating it here (some background articles by my colleague Marco here and here). Suffice to say that it argued for a completely different model putting information from the app layer, such as description of content, into the transport layer, allowing for it to become an instrument for control and surveillance (which is why this proposal got airtime at a human rights conference).

Even though the topic has been put to rest in Study Groups 11 and 13 of the ITU-T late last year, it has understandably left both the technical community and civil society feeling uneasy. Implementing such a change cannot be done incrementally, as it is a fundamental overhaul of the current architecture. Fears of different "Internets" abounded. But are they over? Such a proposal is a symbol of the political ambitions in some parts of the world for a more centralised system and that ambition has not gone away. Many are certain that such a proposal, in some other shape or form, will crop up in a matter of time. Moreover, Huawei has announced that the technology is past proof of concept and is ready for implementation, and that large scale pilots have started in April 2021. This means there is also the risk of authoritarian regimes enforcing it as a domestic standard, becoming the de facto standard for all vendors that want to sell into that market. So what do we do now? It seems that the values of the technical community and civil society coincide, but the language does not. Maybe it is time for us to work closer together?

Mandating Interoperability

A discussion about the best way to maintain an open Internet turned to regulation - about its necessity, inevitability and the potential damage it could cause. A problem that cannot get fixed naturally or through market forces is the market concentration in the tech sector. How can policymakers fix it though?

Cory Doctorow, activist and journalist, explained that market concentration did not happen because of the exceptional products or services of tech companies, but rather due to the high switching costs. Leaving Facebook today means leaving your connections, media assets, own annotations and memories. Yet things didn't used to be like that. In the past, switching costs were very low. Steve Jobs had a team reverse engineer Microsoft's file formats and created the iWork suite to allow people to switch from Windows to Apple. Similarly, we didn't have to leave Myspace before joining Facebook, but could use bots to push messages from the new platform to the old, and read replies.

In recent years however, a plethora of policies, rules and regulations made adversarial interoperability (or competitive compatibility) a felony. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, software patents, rules like tortious interference have made it illegal to do to Apple what Apple did to Microsoft.

Big tech players now have lawyers and lobbyists. When Facebook bought Instagram, it presented it as a camera app to the EU to get approval. Breaking up giants will be slow, difficult and costly. Allowing interoperability might be the answer: mandating interfaces will help new market entrants and lower switching costs.

We are looking at a future where companies have to surrender some profits to managed interoperability versus a future in which companies have to fight unequal wars with tech giants who are getting so large and powerful that what is allowed on the Internet might soon be determined mostly by their terms and conditions, rather than by our laws.

This is the moment where a lot of big tech start getting concerned about the privacy of their users, fearing that opening data flows could allow this data to get into the hands of bad actors (the same tech companies who of course still get away with grotesque invasions of privacy when it suits their pocket).

Cory suggested we need three pillars - mandated interfaces, remedies when interfaces are broken, and strong privacy rules. In addition, we should definitely make sure that laws differentiate between competition for something that gives users more self-determination versus competition for things that take-away or limit users' human rights. This way big tech will not be allowed to evoke privacy laws pretending they are doing so in defence of the users, while it is actually in the interest of their shareholders.

Internet Shutdowns

A lot of sessions at RightCon covered the topic of Internet shutdowns. Sadly, they are becoming a popular tool for authoritarian regimes to control or punish their population, or to silence and retaliate against their critics.

Recently, human rights organisations have been deploying a new tool to fight against shutdowns - strategic litigation. As of December 2019, Access Now has recorded 19 lawsuits in 12 countries. Although not always successful, victories are on the rise. It's important to not that lawsuits against the government are usually high-profile cases that get a lot of media attention, so sometimes even if the case is lost, the effort has not been in vain.

There are several reasons, apart from the obvious (fear of retaliation and lack of resources) that such lawsuits fail. Sometimes it's not possible to even start one, since the lockdown is mandated by the courts. Often, as national security is the go-to justification for the shutdown, governments don't disclose the shutdown order on the grounds of national security, and without access to the order civil society cannot build a case. Litigation is also such a prolonged process, that for shorter shutdowns it might just not be worth it.

Panelists made several appeals. To governments - to show proof that shutdowns actually help for national or anti-terrorist purposes. To society - to become more aware of Internet access's special role in carrying out other human rights and spread this awareness to the courts. To international organisations - to offer help, support and exchange of best practise. Finally to civil society - to not be satisfied with the decisions of lower courts (which are often not independent) and appeal until all avenues are exhausted.

Comments 0

The comments section is closed for articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please contact us.