The 16th annual meeting of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) will be taking place from 6-10 December in a hybrid format. This year's theme - Internet United. Check this page each day for the latest issues, arguments and ideas as they arise at the meeting.

The IGF has a wonderful theme this year - Internet United. Topics are grouped into six categories: economic and social inclusion, universal access, regulation, environmental sustainability, inclusive governance ecosystems and trust and security. As the event goes on, we'll be sharing key moments and takeaways from the sessions we attend.

Does this sound interesting and do you want to actively participate in the IGF sessions? It's still not too late to register. Check out their interactive program and if you've missed any interesting session, take a look at the video recordings.

Day 3: Getting Practical on Internet Resilience

With so many IGF session focused on high-level principles, frameworks or ideas, it can be refreshing to find a session with a more practical focus. That’s what Workshop #260, Internet resilience towards a renewed resilience for society, felt like - an opportunity for some experts in their fields (including RIPE NCC’s Marco Hogewoning) unpack the practical strategies that can be deployed, and the approaches that still need to be developed or refined, to achieve the level of resilience that today’s Internet (and our reliance on it) demands.

Organised by participants from ARCEP and AFNIC, the session kicked off with an intervention from the OECD’s Ghislain de Salins, who noted that organisation’s role as a standardisation organisation “not for technical standards, but for policy”. He highlighted the OECD’s work on six principles of resilience and a policy toolkit for the public sector, as well as the ways in which this public policy work intersected with work by more traditional standards organisations like ETSI or NIST (both of which released technical standards for IoT security in 2020).

Speakers from government (Eglé Vasiliauskaite from Lithuanian government) and the private sector (Google’s Jean-Jacques Sahel) looked at the roles those stakeholder groups can and are playing in contributing to a stronger, more resilient network, while Marco’s intervention focused on the importance of a “security culture”, in which security is prioritised, and the focus is on learning and transparency rather than blame. In the long run, security incidents are an unavoidable fact of life - when they do, our goal should be to look back and be able to say it was totally unexpected and we have made sure it will never happen again.

The other key point of relevance here, for the RIPE NCC, but also the multistakeholder community generally, is this: the danger posed by Internet security events are not only in the events themselves; the reaction of public policymakers to the public’s well-founded outrage and concern can also pose challenges to an open, unfragmented global Internet. Building an effective, all-of-society approach to mitigating Internet security risks will require a significant shift in mindset, but it’s in all of our best interests that we achieve that - this workshop was one more step down that road.

- Chris Buckridge (9 December 2021, 20:00 UTC)

Day 3: Regulation, interoperability and the need for a humble approach

During one of the IGF’s main sessions, titled "Regulation and the open, interoperable and interconnected Internet - challenges and approaches", an expert panel tackled the topic from the perspective of data, content and AI - and it quickly became apparent just how interconnected those topics have become on today’s Internet.

There was a focus on the need for interoperability to support the free flow of data across borders and an examination of the role of standards in supporting interoperability, leading to the inevitable question of how to balance this with security and privacy concerns in an age when data has become more valuable than physical goods. There was also general agreement that today’s Internet has the potential to cause a great deal of harm, yet the solutions to those problems are also often technological in nature (e.g. cryptography, digital signatures, etc.).

The role of AI was a hot topic - the session’s moderator, Jovan Kurbalija, even remarked how AI had replaced blockchain as the IGF’s ubiquitous topic du jour - with an emphasis on the need to better understand how AI is affecting the younger generation as we wade through uncharted territory, along with the need to include a diverse array of people and perspectives in developing AI applications.

Vint Cerf put forth the idea of a kind of “policy sandbox” in which different ideas could be tested and improved, and implored policymakers to take an iterative approach to policy development, reminding us all of the need to be humble as we try to come to grips with these very big, complex and important questions, rather than trying to make perfect policy.

The wide-ranging discussion covered a lot of ground and was a prime example of what the IGF does well - investigating many different interesting topics from different perspectives that all have something valuable to add. And no, there were not a lot of concrete outcomes (but whether that’s an aim of the IGF is still an ongoing discussion).

- Suzanne Taylor (9 December 2021, 14:30 UTC)

Day 3: Non-interference with the public core of the Internet

The pandemic showed how indispensable the Internet has become to our lives and how crucial it can be in times of crisis. To fully take advantage of all the benefits it offers, more people around the globe need to use it, and we need to use it for more things. To do that, we need to trust it will be stable and will work as intended. Shutdowns and other attacks on the availability of the Internet can limit freedom of expression, freedom of assembly but more broadly, as the public might come to view the Internet as unreliable, it undermines the global effort to take up Internet technologies.

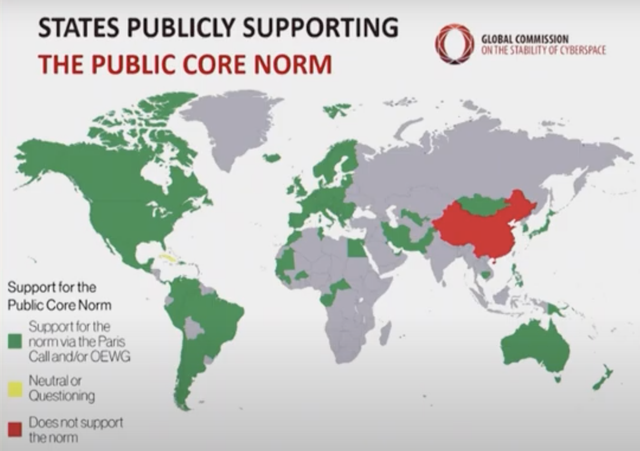

In 2019, at the Paris Peace Forum, The Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace launched a report "Advancing Cyber Stability". It outlined eight norms of responsible state and non-state behaviour and had a significant impact on international discourse. One of these norms is of non-interference with the public core of the Internet: "State and non-state actors should neither conduct nor knowingly allow activity that intentionally and substantially damages the general availability or integrity of the public core of the Internet, and therefore the stability of cyberspace." The public core is defined to include packet routing and forwarding, naming and numbering systems, the cryptographic mechanisms of security and identity and physical transmission media.

At a session titled "Protecting the Public Core" panelists discussed whether it is not so much about protecting the public core of the Internet, which might be interpreted as encouraging government control over the Internet as a means of protection, but a question of non-interference - a restraint from malicious state behavior. The public core of the Internet should not be affected when trying to regulate what happens on the Internet. Wolfgang Kleinwächter cautioned that if you politicise this neutral resource then you add an additional threat to the functioning of the Internet. Bringing geopolitical conflict to the management of the technical resources undermines the stability of the system. According to him governments should use the Governmental Advisory Committee in ICANN or the consultations established within the RIRs and other technical bodies and not interfere in the day-to-day management of critical Internet resources. A few good questions remain: If there are state actions against the public core of the Internet - what should we do, and who should do it?

Sheetal Kumar advised that civil society can play an important role in monitoring and compliance. She shared the example of the work carried out by Global Encryption Coalition in monitoring threats to encryption from around the globe and pushing back against them, publishing research showing the effects of undermining encryption and engaging with policy makers.

Finally, Chris Gibson spoke of his concern about states building capabilities to run their own Internet. They probably do this because they themselves do not trust to function without their control and see a threat from outside. Next, he is also worried that an increasing part of the public core of the Internet is operated by private entities. In the future they could become consolidated - something we already saw with tech giants "on" the Internet. Having a handful of multinationals run the Internet would limit competition and potentially create conflict between the countries these multinationals are based in and the rest.

- Gergana Petrova (9 December 2021, 13:00 UTC)

Day 2: Beyond the Hype of Digital Sovereignty

As Chris Buckridge already reported on this blog earlier in the week, the concept of digital sovereignty is a big theme at this year’s IGF (and really, for several years now in the Internet governance space). During a Town Hall session this morning, a panel of experts and those in attendance tried to take a step back to nail down exactly what we even mean when we use the term digital sovereignty.

Milton Mueller kicked off the discussion with a definition of sovereignty rooted firmly in international relations that dates back centuries, in which the state is the supreme and exclusive authority within a territory and is not subject to external influences. In the digital sphere, he extended this definition to encompass the power of the state to erect borders to protect itself from incoming information, trade protection of digital services and equipment, and control over users’ data. In this view, state sovereignty and individual sovereignty are diametrically opposed.

On the other end of the spectrum, Andrew Campling praised the ability of the state to use digital sovereignty as a tool by which to protect the rights of its citizens, which he sees as being eroded by the tech sector’s large corporations. He argued that the very fact that different states uphold different values makes digital sovereignty absolutely essential, pointing to examples that included the GDPR in protecting European citizens’ privacy rights and mitigating the harms of such regulation as the US CLOUD Act. If the result is a so-called splinternet, he said, then so be it - the most important thing is ensuring citizens’ rights. An attendee echoed this thinking with his comment that different parts of the world have different views on data ownership (including user data), which he said is seen as belonging to private companies in the US, to individual users in the EU, and to the state in China.

The conversation touched on a lot of different points that, while perhaps not converging on a single definition of digital sovereignty, were nonetheless interesting. Chris brought in a concept that was discussed during the panel discussion he participated in yesterday about the difference between digital sovereignty and digital autonomy, and whether autonomy might mitigate the need for sovereignty. Mauro Santaniello wondered whether, in looking at the EU, we need to expand our understanding to include forms of shared sovereignty between multiple states, while Alexander Isavnin asserted that the more countries talk about sovereignty, the less democratic they tend to be, and that sovereignty is really all about controlling the flow of information.

Milton asked who, if not corporations or states, should make the decisions in the digital space and suggested that global organisations supporting the multistakeholder approach to Internet governance, such as ICANN, are best positioned to take on such issues as global access. Finally, Wolfgang Kleinwächter pointed out the need to distinguish between the fragmented (upper) layers and unfragmented (lower) layers of the Internet, and highlighted ICANN’s new terminology of “technical Internet governance” to refer exclusively to governance over the parts of the Internet that are borderless.

With so many differing opinions even on what constitutes digital sovereignty, it’s no surprise that questions about its place in Internet governance are complex and difficult to answer - or why it’s such a hot topic this year.

- Suzanne Taylor (8 December 2021, 15:30 UTC)

Day 2: The Internet’s Technical Success Factors

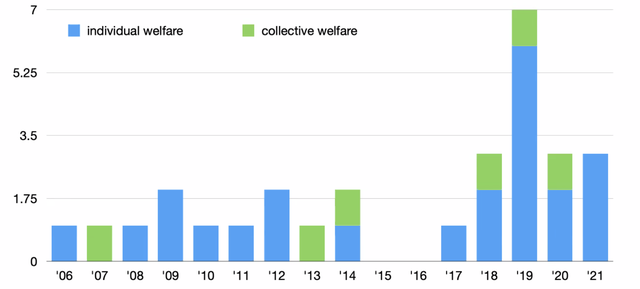

Earlier this year our colleagues from APNIC and LACNIC commissioned Analysis Mason to write a report and investigate the Internet's technical success factors. After a lot of work and many interviews with stakeholders from the community and a number of RIR staff, they presented their findings during a TownHall session today.

The study concludes that the success of the Internet manifests itself through what is described as four dimensions of success. It argues that the Internet has succeeded in scaling to demand, it has been flexible to adapt to changes in underlying network technology and new applications, and that it has shown resilience against shocks.

This report underlines what we have been saying all along - that the past 40 years mark the success of the Internet, not only as a technology suite, but also as evidence that its multistakeholder governance works. As the report opens, we often take the Internet for granted. But look back 20 years. Back then, TCP/IP and the Internet certainly weren't the only technologies around, and many regarded them as a "nice attempt" while arguing for change or to promote their own competitive technologies. As time has passed, many of these technologies are now gone or reduced to niche applications, whereas other services find themselves now sitting on top of a TCP/IP network or replicated by Internet based services.

It might not be perfect and we should always be on the look out for ways to evolve, adapt and make this better. But it can't be denied that so far, this has been a great success, even despite hurting some business cases or earning models.

For more information take a look at the full report here.

- Marco Hogewoning (8 December 2021, 11:00 UTC)

Day 1: Investing in Digital Growth

We can all get behind a drive for a better world and an improved economy. Innovation is often hailed as the holy grail of it all. It determines the economic pathway of countries. Businesses try to chase it, offer the next hot thing that brings them fame, solid market share and profit. Politicians try to create a nurturing environment for such businesses in the hope to reap the benefits of a growing economy.

So what fosters innovation? First you need a stable and predictable legislative environment in order to attract investors. Then you need the investors themselves. Panelists at a high level session on investing in digital growth and enabling capacities pointed out that Europe is still underinvesting in the ICT sectors compared to other major economies (e.g. the US and Japan).

Countries have to nurture a vibrant entrepreneurship ecosystem, supporting it though various programs. And course there's the need to build modern infrastructure around those programs to ensure access. Panelists also stressed the importance of human capital. Skilled people are needed not only to build and support the requisite infrastructure, but also to make use of it, continuing to innovate once it's there.

Finally, there was a call not to forget to help our neighbours out - as the digital gap between rich and poor economies - but also within economies themselves - limits the benefits technology brings.

Fostering innovation is not such an easy task. One panelist remarked that the world today is about to face a double transition - that of digital and green. Combining both will be an important growth engine, but will also pose lots of new challenges. Greater investment programs and collaboration between public and private players is going to be essential.

- Gergana Petrova (7 December 2021, 16:00 UTC)

Day 0: Headfirst into Digital Sovereignty

“Day 0” of an IGF is always an interesting, motley collection of events - largely comprised of sessions that weren’t “multistakeholder” enough to meet the requirements that are applied to sessions in the “formal” IGF programme, they nonetheless tend to provide some of the more focused discussions of the week, often drawing on expertise and perspective from a single region, stakeholder group, or in some cases, organisation. They can also give some insight into the issues that are likely to dominate discussions for the remainder of the week.

That was definitely the case this year, and many of the day’s discussions found their way quickly to the concept of “digital sovereignty”, a phrase (sometimes used interchangeably with “digital autonomy”) that has become a focus of many Internet regulatory and governance debates over the past year.

One factor in this has been the European Union’s regular use of the term - with the IGF taking place in an EU Member State (as well as online), EU policy debates were always going to be a significant factor in this year’s event, and they were front and centre in one of the day’s first sessions - ‘In the search of a golden mean – different perspectives on the regulation of digital markets’.

Organised by Poland’s Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers, the session dug into different approaches and priorities in Internet regulation. Both the resident “Big Tech” representative (Google) and a representative of the local start-up sector agreed that greater harmonisation and simplification of laws should be a priority. Discussants differed though on the degree to which Europe was going its own (anti-business) way with regulation, or was simply the leading edge of a far more globally aligned shift toward pro-active regulation of Internet services and service providers. Katarzyna Szymielewicz, of the Panoptykon Foundation, lamented the lack of a holistic view of the many issues related to Internet usage, and that platform providers had not been taken a more pre-emptive approach to heading off regulation by addressing the concerns raised by some of their business models.

Another session which drilled down on the idea of digital sovereignty was ‘Global Road(s) to Digital Sovereignty’, which drew on interventions from government and academia to consider what is meant by digital sovereignty and what factors are driving the current surge in state interest. Paul Timmers regards this surge as a response to external factors - the challenge of international platforms to national sovereignty, the increasing risk of cyber incidents or attacks - but sees benefits in the fact that this is happening at the global scale, mitigating the risk of fragmentation or different states applying sovereignty measures in different ways (though other speakers were less convinced of such alignment).

As noted above, digital sovereignty is a topic that will get a fair bit of attention this week, in sessions such as ‘The risks of pursuing digital autonomy’ (on Tuesday at 14:30), ’Beyond hype: what does digital sovereignty actually mean?’ (Wednesday at 10:45), and the Main Session on ’Regulation and the open, interoperable, and interconnected Internet - challenges and approaches’ (Thursday at 11:15). As a concept with the potential to create some pretty dramatic shifts in how the Internet is run and regulated, it’s an issue worth paying attention to.

- Chris Buckridge (6 December 2021, 20:00 UTC)

Day 0: GigaNet's take on Internet Freedom

Another interesting presentation focused on rankings of Internet freedom. Rankings in general can be useful as a tool for comparing countries, turning complicated phenomena into more unambiguous measures, and, not least, as an instrument that can affect a country's international status and even the amount of aid it receives. Some rankings aim to measure and compare (FH Freedom on the Net), others prioritise framing of the list over executing a comprehensive analysis (RWB Enemies of the Internet List) and still others try to encourage action (RDR Corporate Accountability Index).

Internet freedom is a very contested concept. Freedom of access facilitates the delivery of government services and distance education, which is why it is more widely accepted by states. Freedom of use - i.e. the right to express opinions, share and receive information, etc - is more debatable. A lot of rankings assume the Western-leaning perspective that democracy and the Internet go hand in hand. In some cases however, the Internet can be used to strengthen authoritarian regimes. The authors believe the rankings don't adequately acknowledge invasive Internet policies and public administration practices implemented in democracies, and at the same time lack analytical complexity to evaluate and give enough credit to policies and public administration practices in non-democracies.

Lastly, the paper expresses wishes for more transparency about methodological changes of rankings that would allow a correct long-term analysis of trends. Some of the participants suggested that rankings should also disclose their sources of funding.

- Gergana Petrova (6 December 2021, 19:00 UTC)

Day 0: GigaNet's take on Privacy Settings

GigaNet, the network of academics doing work on Internet governance held their annual symposium parallel to the Global IGF.

An interesting talk focused on the evolution of privacy through the lens of privacy controls. It is worth noting what a powerful tool privacy settings are, as most users don't bother changing the defaults. Sometimes they can reflect societal attitudes. For example, Facebook's change of the default settings for teens, initially, and then for all, from "public" to "friends" reflected a broader societal shift towards more privacy. But the public's best interest is usually not the guiding principle.

After analysing multiple Facebook Newsroom articles, Chelsea Horne noticed their rhetoric of “choice and control” - meaning they give users the agency and autonomy to decide on their level of privacy. They then use this to absolve themselves of responsibility when facing pressures from regulators or society or when in legal hot waters. Research has disproven the idea of the "empowered user", as they have little control over the options they have available and switching platforms is not a viable alternative.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal and the implementation of the GDPR let to a marked increase of Facebook Newsroom articles on privacy in 2018 and the following years.

The presentation delved into the so-called "dark patterns" defined by Harry Brignull as the deceptive practices used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn't mean to. Those can be asking tricky questions on forms, sneaking items into your basket, disguised ads, price comparison prevention, and so on (see the full list here).

Chelsea Horne's paper focused on "Privacy Zuckering" - designing difficult to navigate privacy settings and setting very permissive defaults - leading to users sharing more information about themselves than they intended to. In particular, it talked of the two largest FTC fines. The first was when Facebook failed to inform users that even if they select the most restrictive privacy settings, Facebook could still share their information with the apps of the user’s friends. The second was when Facebook misrepresented users’ ability to control the use of facial recognition technology since the setting for facial recognition was called “tag suggestions” and was enabled by default.

The research leads to some thought-provoking conclusions, but leaves many questions unanswered. Are fines truly a powerful sanction or purely the cost of doing business?

- Gergana Petrova (6 December 2021, 16:00 UTC)

Comments 0

Comments are disabled on articles published more than a year ago. If you'd like to inform us of any issues, please reach out to us via the contact form here.